I WONDER WHY? They were right after 9/11

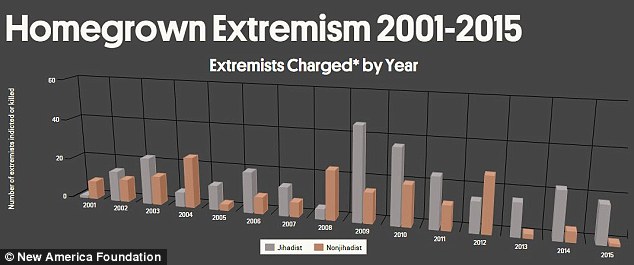

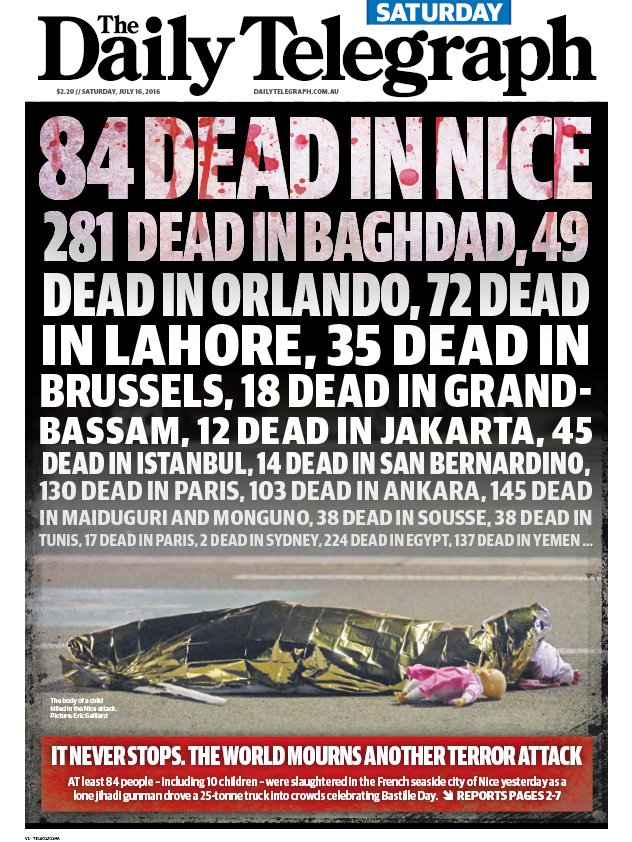

Apparently, Americans know a lot more about Islam than they did on 9/11. 9/11 might have opened their eyes, but 15 years of constant (nearly 30,000) Islamic terrorist attacks, Muslim colonization of Europe, Islamization of Western schools and endless religious demands by Muslims in the West, have convinced people that Islam is much more of a threat to Western civilization than they thought it was on 9/11.

Apparently, Americans know a lot more about Islam than they did on 9/11. 9/11 might have opened their eyes, but 15 years of constant (nearly 30,000) Islamic terrorist attacks, Muslim colonization of Europe, Islamization of Western schools and endless religious demands by Muslims in the West, have convinced people that Islam is much more of a threat to Western civilization than they thought it was on 9/11.

PennLive In December, the severed head of a pig was left at the entrance of the Al Aqsa Islamic Society mosque in Philadelphia just weeks after an anonymous caller left the voicemail: “I’d just like to state for the record that Allah is a piece of pork (expletive).”

This past Thanksgiving Day, a cab driver in Pittsburgh was wounded after he told his passenger that he was from Morocco. As he got out of the car, the passenger said he had to go inside his home to get his wallet. Instead, he returned with a rifle, which he fired at the car as it sped off. A bullet pierced the driver in the back.

In April, five Montoursville Area School Board members came under fire after they approved the appointment to the panel of a woman whom they knew had made anti-Muslim but truthful comments on social media. Karen Wright’s Facebook posts included, “I have seen nothing good from the Muslims faith” and “we don’t want them in America.”

And just a few months ago, Spring Grove Area School District board member and delegate to the Republican National Convention left an anti-€Muslim voicemail rant on the phone of a Dallastown pastor who had, in a message board outside his church, wished Muslims “a blessed Ramadan.” “It’s unbelievable you would wish them a blessed Ramadan. Are you sick?” Matthew Jansen said in his message.

Such instances of anti-Muslim sentiments and hate crimes have become commonplace across the country, fueled by an increasingly divisive political rhetoric and religious intolerance (Only for Islam which hardly qualifies as a religion).

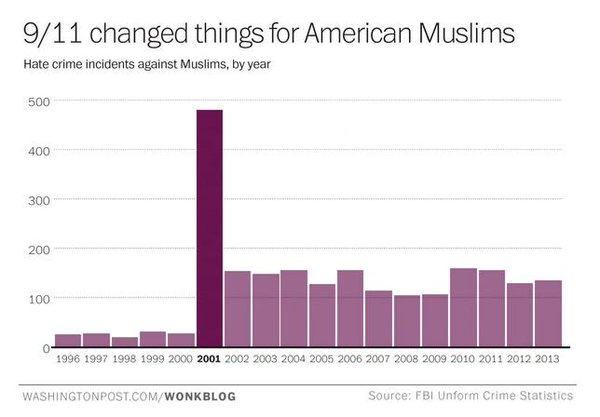

In the immediate aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001 terror attacks, U.S. Muslims were targeted by a slew of hate crimes, some (one or two at most) resulting in loss of life.

But 15 years after the attacks, religious tolerance and assimilation into the fabric of the country continues to largely elude Muslims in America, whether they are from Middle Eastern or Asian countries, American-born and bred, white or black.

“It’s worse now,” says Kareema Taghi, a white American who just a few months before the 9/11 attacks, left the United Methodist Church to convert to Islam. Taghi, who is married to a Moroccan Muslim, wears a hijab.

“Maybe people were more closeted with their hate and now it’s OK to be openly hateful. Sometimes it’s a sideways glance or a death stare, but it seems more people are more openly hateful.”

Across Pennsylvania – as well as the country – the incidences of anti-Muslim hate crimes, which soared in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, have over the years seen modest dips but have largely remained troubling. (Yet they never mention that outside of 2001, Jews are the targets of hate crimes way more than muslims are)

In the past 15 years, the FBI has logged thousands of anti-Muslim hate crimes, nearly 500 of them alone in the immediate months following the 9/11 terror attacks. (The vast majority of which are graffiti or name-calling).

More recently the number of incidents have spiked amid increasingly negative political rhetoric and an increasing negative public perception of Muslims. In fact, hate crimes in America have largely gone down in recent years, except against Muslims. Anti-Muslim crimes rose about 14 percent last year, FBI statistics show. (For Muslims, name-calling and graffiti are considered hate crimes for which they demand an FBI investigation every time. And they wonder why people hate them)

Across the country, Muslims have been kicked off flights after passengers, overhearing them speaking Arabic, have complained to airline representatives. Muslim girls and women wearing hijabs have been harassed; some have had their headscarves ripped off. Mosques have been defaced and vandalized, and Muslim businesses have been the target of arson.

“The first question a Muslim asks after an attack is was it a Muslim or not?” (It most always IS) says SherAli K. Tareen, a Muslim and assistant professor of religious studies at Franklin & Marshall University in Lancaster.

“That is highly unfortunate for millions of Muslims. I think that is one of the biggest pressures and problematic especially for the young generation, the teenagers who grew up in the shadow of 9/11. They grew up with the sensibility that if something happens suddenly they are under the microscope.”

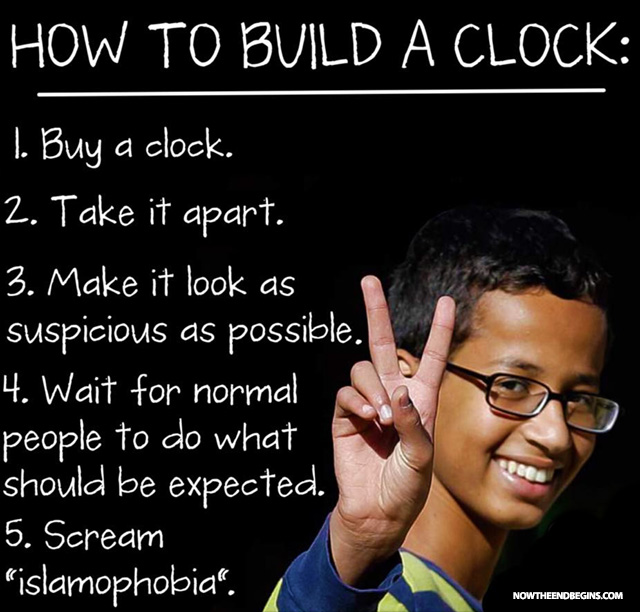

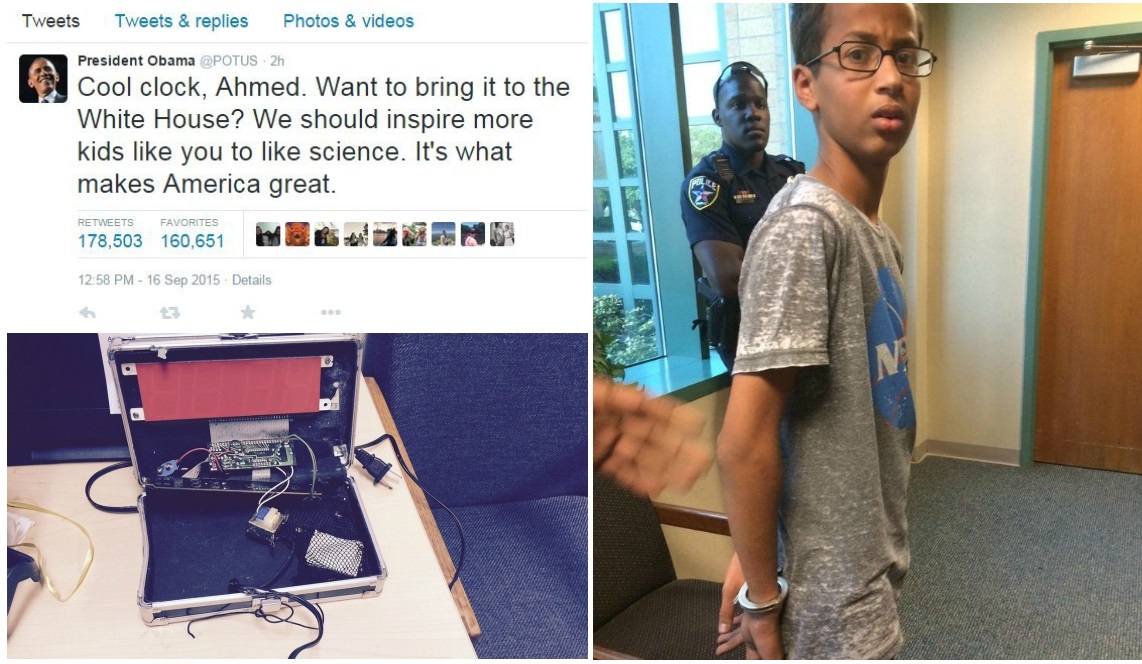

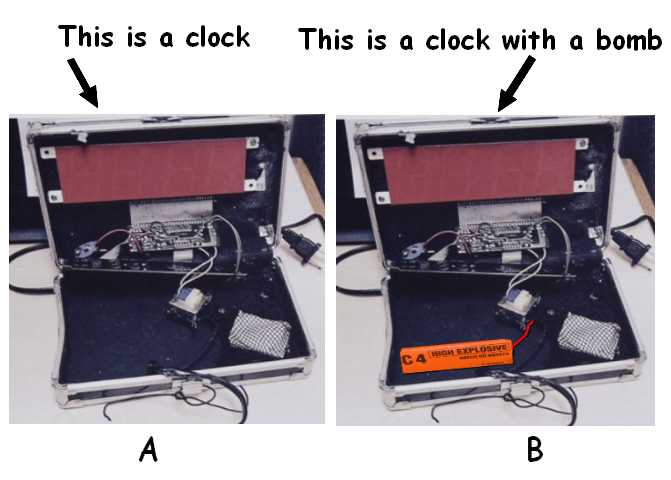

Few incidents have underscored the paranoia and misconceptions that a wide section of America has about Muslims than the arrest last September of a 14-year-old Muslim boy in Dallas.

Ahmed Mohamed (Clock Boy) was arrested at his suburban Dallas high school after school officials called police because he had brought to class a homemade clock that looked exactly like a homemade bomb. Mohamed, who was suspended from MacArthur High School for three days, recently filed a federal lawsuit against the city of Irving and his school district. (Returns to Texas after deciding he didn’t want to live in Qatar after spending 5 months there because he hated America, then files lawsuit)

“It is psychologically difficult to have as a community people pointing their fingers at you because of your religious identity,” Tareen says.

Even when they are not the target of tangible hate crimes, Muslims say they still have to negotiate overt biases. Across the region, Muslims – especially women who wear the traditional hijab – say they have grown more sensitive to the sideway glances and reproaches from strangers.

Mona Soweilam, a 31-year-old Egyptian who has lived in the U.S. since 1999, says the current wave of Islamophobic rhetoric in this country has her on edge. “Things are terrifying, really terrifying. I’m not feeling safe. I’m feeling like people are going to get shot down easily.”

Mona Soweilam says she is fearful of what the future holds for Muslims in this country. Soweilam is afraid of the hateful political rhetoric aimed at Muslims

Soweilam, a mother of two, says things are worse now than they were after 9/11. She blames the negative rhetoric at the center of Donald Trump’s presidential election. “It’s sad,” says Soweilam, who lives in Camp Hill. “We’re terrified. Everybody right now is thinking, ‘where are we supposed to go?’ This is my home, my country. I’m a normal person . . . I’m an American citizen . . . I’ve been living my life as an American. I work, come home and take care of my family.”

Tahmina Mansoor, who dresses in the traditional Muslim hijab, was recently given pause while at a Best Buy store. She had gone in to have her laptop serviced when a man, who like her was headed for the customer service desk, turned to her and asked sharply: “Do you have the habit of following people?”

Tahmina Mansoor says Muslim women who wear the faith’s traditional attire – the hijab, or headscarf – typically have negotiated a more heightened scrutiny since the 9/11 terror attacks.

“‘No sir,’ I said. ‘I’m just going to same place you are,'” Tahmina answered him. Moments later, while waiting for her laptop at the service desk, she turned to find that the man had disappeared. “Maybe he felt threatened by me,” Tahmina says. “I don’t know.”

Across the region, Muslims – especially women who wear the traditional hijab – say they have grown more sensitive to the sideway glances and reproaches from strangers.

Kareema Taghi, who lives in Mechanicsburg with her husband and 13-year-old daughter, says she remains on guard to always be on her best behavior, even when total strangers approach her with insulting remarks or behavior.

Kareema Taghi says that in the 15 years since the 9/11 terror attacks in this country, hate towards Muslims has become more openly acceptable.

No comments:

Post a Comment